Eyes Open. Shoot First. Think Later. Godlis in Conversation with Richard Boch

“I was committed to being the guy that walks around with a camera shooting pictures of what he sees.” Photographer GODLIS talks life on St. Marks, CBGB’s, and his new book.

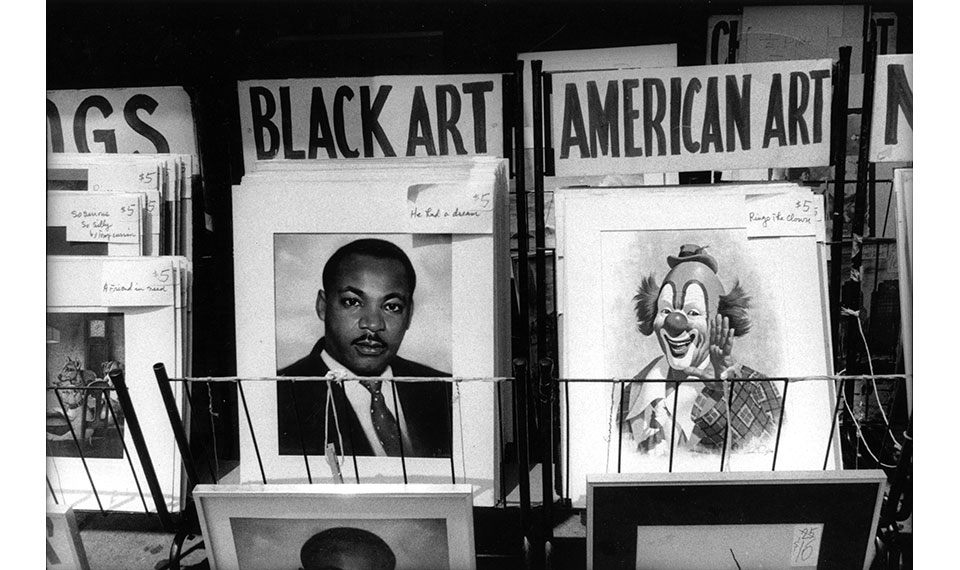

New York City—downtown in particular—the night-as-day inversion held a grip on so many of us that coming of age in the mid-to-late ’70s was a bit of a white-light experience. Camera in hand, the photographer David Godlis, who came to be known simply as GODLIS, was able to navigate and capture that topsy-turvy. He arrived in the East Village from Boston where he had studied at ImageWorks in Cambridge. St. Marks Place was still locked in the throes of a ’60s Bohemian mayhem while a few blocks away at Bowery and Bleecker Street a new world was exploding. The surrounding blocks and the streets in between were rich for the taking.

Whether his eye was doing a single-focus scan of the wild time nighttime of the Bowery’s punk petri dish CBGB or wandering the bright-light noontime of midtown, lower-Manhattan or the city’s lost nether regions, Godlis’s shutter finger was at the ready. I remember walking through CB’s front door and pushing past the bar. The band Television was exiting a dressing room only slightly larger than a doghouse and stepping on to the tiny CBGB stage. A guitar slowly began to moan until it let out a scream. The band was ready. So was David Godlis.

The city was such a non-stop thrill-ride revelation that I don’t know how any of us slept, or if we ever did. Looking through his brand new book, Godlis Streets, or revisiting his 2016 masterpiece History is Made at Night, the images offer a beautiful variant of photojournalism through the eyes of an artist. The past becomes a present-day dreamscape allowing me to re-experience a world I loved, rather than reminisce a world gone by.

Let’s let Godlis tell us how he makes that happen.

Richard Boch: Hi David. It’s great to catch up and talk about your new book, Godlis Streets. First let’s hear about where you started out and how you wound up living on St. Marks Place.

David Godlis: Well, I used to hang out on St. Marks in the ’60s, when I was a teenager, for records, and the Fillmore East for shows. But when I first came back to the city from Boston in 1976, I got a day job as a photographer’s assistant in Times Square and I was staying at a friends place on East 20th Street, which was also an easy walk to CBGB. I first went looking for an apartment in SoHo but was priced out at $225 a month! I thought I could do better, so I went looking in the neighborhood I used to hang out in. I found a place on St. Marks for $200 that had extra room. I saw what I thought was photographer Roberta Bayley’s name on the buzzer. She was working the door at CBGB’s at the time, but was in England when I called her to see how the building was. So I just put down my deposit and moved in. When she came back, we were living in the same building—and we still are.

RB: From what I can see, you’ve always loved street photography—the work of Brassaï and Arbus along with the work of Robert Frank. The spirit of Brassaï seems so connected to the spirit of what you captured at CBGB—that burst of sound, vision and word. Did you feel that connection? Is that where your “Eyes open. Shoot first. Think later.” credo came into play?

DG: Yes, once I knew what street photography was, I knew that’s what I wanted to do. Of course, I had dreams in my head of what that meant—I was committed to being the guy that walks around with a camera shooting pictures of what he sees. And yes, I felt the direct connection to Brassaï, as I did with Frank and Arbus. I also had the movie Blow-Up in my head with visions of David Hemmings printing in the darkroom after shooting Vanessa Redgrave. It seemed like a cool life. I always loved music and photography, so it was just a stroke of luck that the new Brassaï book Secret Paris of The 1930s came out in 1976, just as I began hanging out at CBGB’s. It all of a sudden occurred to me that I could apply Brassaï’s night-shooting technique to taking street pictures of punks at CB’s. The “shoot first think later” might have come from photographer William Eggleston, who was a friend of Alex Chilton who was often performing at and hanging at CBGB. Eggleston says he never takes more than one shot of anything. At the time he had the very first color photo show at MoMA.

RB: Your book History is Made at Night was focused on the scene inside and outside of CB’s. The photos capture the strange beauty, not to mention the vibe of that moment. It’s not much of a stretch to see how those images connect to your work in Godlis Streets. What’s the show and tell here?

DG: Well I like photographing people—people on the street, people out at night, filmmakers at the NY Film Festival. That would be the through point of what I do. But it was on the Bowery, with everyone lit up by street lamps, shooting at slow shutter speeds, that I thought was most appropriate for the punk scene. It gave those pictures a unique look, and fit well with the music I was hearing. Like Television or Richard Hell or Patti Smith. I think of those pictures as a variation on the Velvet Underground’s sound in the song “White Light, White Heat.”

RB: You seem to be a guy with a routine. You’ve lived on St. Marks for over 40 years. You eat breakfast or lunch around the corner at B&H every day. There was a period that you were at CBGB every night, and possibly walking the streets with your camera by day. What’s the routine today?

DG: You’re not too far off. I am a man of routines. Same color clothes–black. Same shoes–Nike. Same breakfast–peanut butter. The day used to include film developing but now it’s a lot of processing pictures on the computer. Of course, in Covid times everything’s a bit up in the air. But I wear the same black mask and drink the same coffee in Astor Place. And when I go out the camera goes with me. I like to try walking different streets, but I do have some favorites—Fourth Avenue, First Avenue and St. Marks Place.

RB: Robert Frank, the master photographer and documentarian once said, “Black and white are the colors of photography.” Are those your colors too?

DG: Well, that’s how I first learned photography using Tri-X Film. I grew up on black-and-white TV and black-and-white movies. If you shoot color, someone wearing purple in the background can throw your whole picture off; with black and white that doesn’t happen. Very basic and it’s so classic, like classic Coke. The Rolling Stones say it perfectly in “Paint it Black” after the opening drum beat—“I see a red door and I want to paint it black. No colors anymore, I want them to turn black.” I almost titled this book that.

RB: Thanks, David. It’s been great having this conversation. Your new book, Godlis Streets, comes out November 17, 2020—I only wish there was going to be a big book release party. What’s your wish?

DG: Yeah we gotta do the book party virtually. But that will be fun with Luc Sante and Chris Stein. Then with the book in your hands at home, you can have the real experience. Just turn the music up loud, sit back with the book and give your eyes a jolt.

Godlis Streets is published by Reel Art Press. For further information and full list of stockists visit reelartpress.com.

PHOTOGRAPHY © GODLIS

WORDS Richard Boch

Richard Boch writes GrandLife’s New York Stories column and is the author of The Mudd Club, a memoir recounting his time as doorman at the legendary New York nightspot, which doubled as a clubhouse for the likes of Jean-Michel Basquiat, Keith Haring, Debbie Harry, David Byrne, among others. To hear about Richard’s favorite New York spots for art, books, drinks, and more, read his Locals interview—here.